In England’s Lyme Bay, fishermen, conservationists and the government are negotiating new ways to protect fishing and nature

Few people have a better view of what happens under the sea’s surface than a scallop diver.

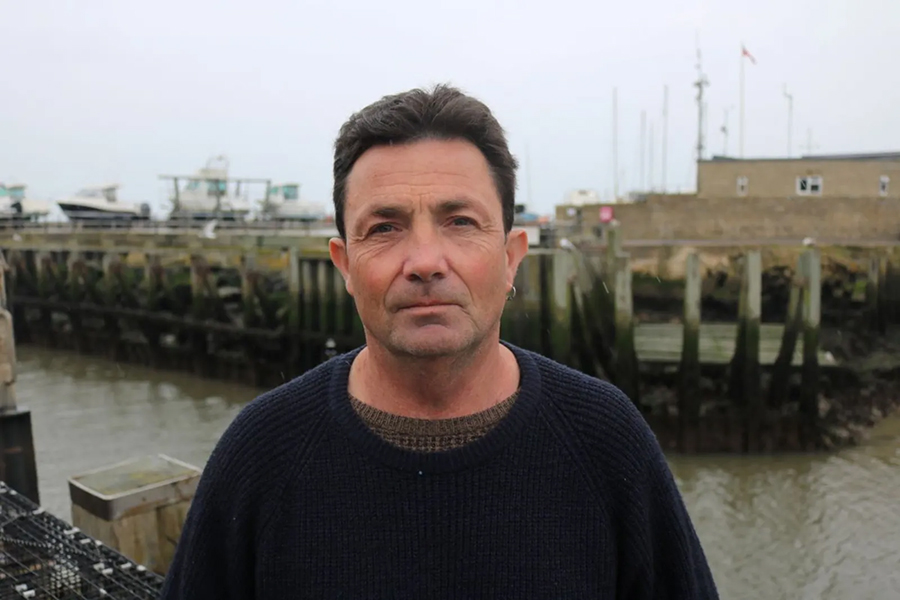

Having foraged for the shellfish off England’s south coast since the 1990s, John Worswick has witnessed the destruction of seabed habitats as large dredging boats hoovered up scallops beyond the golden cliffs of Dorset’s Jurassic Coast.

“The reefs were disappearing,” said Worswick, now in his mid-60s, who lives in the small harbour of West Bay and dives for scallops in Lyme Bay, an area of the English Channel.

“Every year it was just getting worse and worse.”

But things changed in 2008, when the government banned dredging and bottom trawling in 206 square km (80 square miles) of Lyme Bay, creating a Marine Protected Area (MPA).

The area under protection was later expanded to 312 square km (120 square miles) by an overlapping conservation area.

Dredging and bottom trawling involve heavy nets being towed along the seabed. These methods have been widely denounced by conservationists as destructive to marine habitats.

After the ban came into force in Lyme Bay, Worswick said he noticed ecosystems grow back significantly within just a few years.

Corals called pink sea fans sprouted back up from the seabed’s surface. Scallop numbers increased, too, he said.

“It’s quite nice to realise how quickly nature can recover given the opportunity,” Worswick said.

Academic research has found that the number of species – and their diversity – rose in the Lyme Bay MPA in the decade after it was established.

Lyme Bay is being hailed as a model of how to promote sustainable fishing and protect biodiversity in a way that involves local communities, as many small-scale fishermen remain fearful of overregulation, and for the future of their industry.

Following a landmark U.N. biodiversity pact agreed last year to protect 30% of the world’s oceans by 2030 against threats from pollution to overfishing, scrutiny is growing over the extent to which MPAs should be protected and monitored.

Marine conservationists say Lyme Bay’s approach should be replicated because it outright bans destructive bottom trawling, setting it apart from most other MPAs across Britain and Europe, which tend to have narrower or limited restrictions.

Lyme Bay’s ban on bottom trawling

There are 178 MPAs in England – covering 40% of its seas – yet only 8% of English waters prohibit bottom trawling, according to the latest data shared by the Marine Conservation Society, a charity focusing on ocean issues.

In response to questions, the Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs (DEFRA) said it is working to ensure England’s MPAs are “properly protected” by 2025, including by using byelaws to “manage all types of harmful fishing”.

DEFRA recently announced three pilot Highly Protected Marine Areas, which ban all forms of fishing and activities such as construction.

But activists have criticised the government’s decision to pilot the programme on only three sites rather than five as initially planned, which an independent review said was the “bare minimum” on which to judge the project.

Hugo Tagholm, director of advocacy group Oceana UK, said it was a “disappointment”, and that England is “lagging behind our neighbours in Europe” with the European Union (EU) having committed to 10% of its seas being highly protected by 2030.

Benefits of Marine Protected Areas

In West Bay, fisherman Matt Toms explained how dredging lifted away habitats and allowed seafloor nutrients to be washed away with the tide.

Toms said he had seen a lot more fish in the area – like black bream breeding in the bay – since bottom trawling was banned.

“If the food’s there then the fish will be there,” said the 53-year-old, who has fished in the area for 35 years.

In the decade after the Lyme Bay MPA was established, the number of species within the protected area increased by 39%, compared with a 5% drop outside the zone, according to a 2021 study published in the journal Diversity and Distributions.

The research also found that the MPA experienced a 65% rise in ‘functional richness’ – a key measure of ecosystem diversity.

“It’s just really fundamental: if you leave seabed habitats alone, they will recover,” said Emma Sheehan, co-author of the study and a marine biologist at the University of Plymouth, whose team monitor the area with the help of local fishermen.

Jean-Luc Solandt, a marine biologist at the Marine Conservation Society, said Lyme Bay was an example of a well-managed MPA because there was scientific monitoring to understand the environmental impacts of protections, and collaboration with local fishermen.

“What’s happened in Lyme (Bay) should happen everywhere,” said Solandt, a specialist on MPAs.

However, some fishermen in Lyme Bay were frustrated when the MPA was created because it suddenly curtailed their rights to fish, and many more have been disillusioned with the government’s overall management of the industry, saying that they are often overlooked and their concerns ignored.

But fishermen’s engagement with conservationists and regulators has since improved – particularly with the creation of a fishermen’s community interest company (CIC), which provides logistical support and advocates on issues such as equipment regulations.

Frustrations with government and Brexit

About 10 local fishermen – spread across four ports in the counties of Dorset and Devon – interviewed in April were mostly positive about the protections afforded by the MPA.

The majority are not involved in bottom trawling or dredging but use “static” methods like nets, pots and traps which are still permitted. They said they have benefitted on the whole from better catches of valuable fish and shellfish like lobster.

However, the fishermen recalled that the announcement of the Lyme Bay MPA in 2008 was divisive. Some welcomed it as dredging had been increasing, mostly by boats from outside the area, which undermined local voluntary agreements to protect the reefs.

But others were angered by the change, especially trawlers.

“I went from having an income to not having one,” said Angus Walker, a fisherman who had to decommission his trawler and instead turned to catching crabs and lobsters to make a living.

“There was no support whatsoever, no compensation,” said Walker, who is now harbour master in the village of Axmouth.

A few years later, the Blue Marine Foundation – an environmental charity – created a forum to improve communication between fishermen, conservationists and regulators, and funded new infrastructure including a lobster storage facility.

This paved the way for the creation of the CIC in 2022 to directly represent the fishermen, allowing for more frank and constructive meetings with officials after years of frustration.

Mandy Wolfe, a Californian who created the CIC after working for the Blue Marine Foundation, said it was a case of “wiping the slate clean” and starting a new kind of model.

To her knowledge, the 49-member CIC is the first of its kind to combine practical support – like having a van to take fish to market – with things like advocacy and public engagement, such as a schools programme to encourage new blood into fishing.

One member, Aubrey Banfield, said the CIC has allowed fishermen to advocate with a more united voice, despite usually being “secret squirrels” when it comes to their work.

Members are particularly concerned about the increased amount of static gear being used, with huge nets getting in the way of their work, as well as quotas for catching sole having more than doubled since 2015, drawing larger boats to Lyme Bay.

The Marine Management Organisation (MMO), which manages England’s fishing fleet, said it has worked extensively with the CIC, adding that such engagement is increasingly important to support “a successful fishing industry … balanced with the need to protect our precious marine environment”.

But trust in the government will take time to rebuild.

Fishermen felt betrayed by Britain’s post-Brexit trade deal with the EU, which the national industry body said in 2021 had sold them out.

One particular disappointment, according to some of the fishermen, was that EU boats were permitted to operate up to six nautical miles from Britain’s coastline, half the 12-mile limit that fishermen had considered to be a ‘red line’ in negotiations.

“(It) was absolutely devastating for the industry,” Banfield said.

Bottom trawling threatens ocean biodiversity

Lyme Bay was the first large-scale MPA in Britain to protect its whole area from bottom trawling, a major break from the “feature-based” approach used in most MPAs in Europe.

“Which means you draw a box and then you’re only protecting specific patches that you’ve identified,” such as rocks or seagrass, said Sheehan from the University of Plymouth.

Sheehan said her team’s research found that areas between features such as reefs are more important than previously thought, and that a “whole-site” approach could make MPAs more resilient as climate change makes extreme weather more common.

For example, after severe storms in 2013 and 2014, biodiversity recovered quickly in the Lyme Bay MPA compared with areas outside of it that had not banned bottom trawling, a 2021 study in the journal Frontiers in Marine Science found.

The whole-site approach will now be used in the government’s stricter pilot Highly Protected Marine Areas.

“We need to understand what an area looks like without fishing or other human activities so that we can really assess how our marine protected areas … are doing,” Sheehan said.

Industrial-scale fishing – especially bottom trawling – has been a major threat to ocean biodiversity around the world, studies show, yet is still permitted in most MPAs.

Tagholm, Oceana UK’s director, said big factory ships are “indiscriminately pillaging and harvesting our ocean” and, in doing so, “robbing the livelihoods of our fishing communities (and) robbing the abundance from our seas”.

As well as degrading the seabed for fish, trawling generates more bycatch, destroys habitats, eliminates species complexity, fuels climate change – by releasing planet-heating carbon from the ocean floor – and is bad for water filtration, according to Solandt of the Marine Conservation Society.

“We’re really starting to understand that the sea is really essential for a healthy planet,” he said.

“If we don’t do marine protected areas, and we don’t start stopping bottom trawling, and we don’t start reducing water quality problems, we will really suffer as a species ourselves.”

Fears for the future of fishing

In east Devon’s picturesque village of Beer one evening in April, children gathered to watch boats come onto the beach as the sun started to set.

Fishermen showed them the day’s catch – lobsters, crab and whelks – much of which is sold at a shop at the top of the beach by a local business, Beer Fisheries Ltd.

“We go out, we fish, we catch for a day, and we sell it,” said the owner Marc Newton, 34, a fourth-generation fishmonger whose family has been fishing in the area since the 1600s.

“We don’t have any waste. That’s sustainability to me,” said Newton, who is also a member of the CIC.

While most local fishermen say they have benefitted from the MPA, many are worried about the viability of their industry – from increasingly onerous regulations to the fact the workforce is ageing.

They also fear losing out to multinational companies – a handful of which own the majority of England’s fishing quota – and remain wary of partners in government and conservation.

As conservation groups push for stricter MPAs nationwide – including “no-take” zones to revive crucial biodiversity areas – many fishermen in Lyme Bay said they are worried these organisations want to further restrict their work.

Such concerns are among the main reasons that CIC members want more influence over how regulations are made – and what happens in their local waters.

Newton said he believes the CIC should be replicated in other coastal communities, to allow other groups of local fishermen to contribute to the management of their own patches.

“They’ve got a life there, a career. They want the fish to be there next year,” he said.

“We’re not hammering what we’ve got here, we’re looking after it for generations to come.”

Reporting and Photography: Jack Graham. Editing: Kieran Guilbert and Laurie Goering.