The number of people working in renewable energy has nearly doubled in 10 years as the world begins its transition away from polluting fossil fuels like oil and gas, new research showed.

Jobs in renewables hit 13.7 million in 2022, including in solar, bioenergy, hydropower and wind, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) and the International Labour Organization (ILO) said on Thursday.

Yet the rise of clean energy raises questions. Who has access to these new jobs? What skills do they require? How much do they pay? And what can be done to help communities that rely on traditional industries?

Context spoke to climate experts to find out more about what the changing energy mix means for jobs.

How many green energy jobs are there?

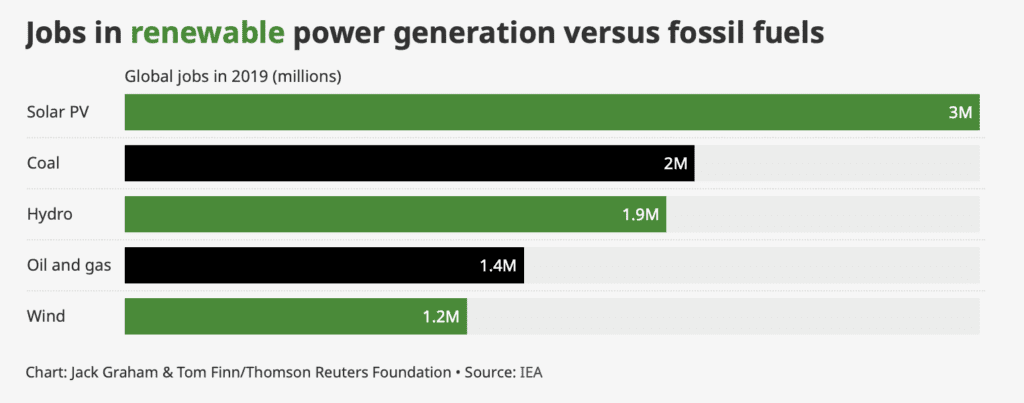

Some 65 million people work in the energy industry worldwide, and clean energy workers now account for more than half of them, the International Energy Agency (IEA) says.

The IEA uses a broader definition of clean energy jobs, including roles with low-carbon but non-renewable technologies such as nuclear power, as well as jobs in the broader energy sector like those in energy efficiency.

“It’s clear that the clean energy economy isn’t around the corner, it’s here today,” said Joel Jaeger, a research associate at the World Resources Institute, a think tank.

If the energy transition happens in line with the goal of reaching net zero by 2050, the IEA predicts an additional 30 million workers will be employed in clean energy by 2030, compared to some 13 million jobs lost in fossil-fuel industries.

This transition could also change the gender imbalance of the energy industry. IRENA said women make up 32% of the workforce in renewable energy, compared to 22% in oil and gas.

In solar, the fastest-growing renewable energy sector, women have 40% of the jobs, it said.

Where are the green jobs located?

Clean and renewable energy jobs are located all around the world, but the biggest and fastest-growing workforce is in Asia.

China, home to almost 30% of the global energy workforce, dominates the manufacturing of solar panels – also known as photovoltaics (PV) – and employs nearly half of those working in the field, according to the IEA.

“Different regions are further along than others,” said Jaeger, pointing out that in the Middle East and Russia more people are employed in fossil fuel jobs.

“Emerging market and developing economies are going to have more jobs no matter what, because those economies are generally a lot more labour-intensive,” he said, citing the example of India where clean energy jobs now outnumber fossil fuel roles.

China’s domination of solar PV manufacturing was partly made possible because the equipment is easier to export than other technologies, said Aurelien Saussay, an economist at the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics.

Wind turbines, by comparison, have strong regional hubs in northern Europe and the United States which are less threatened by competition from Asia, he said.

Are they high-quality jobs?

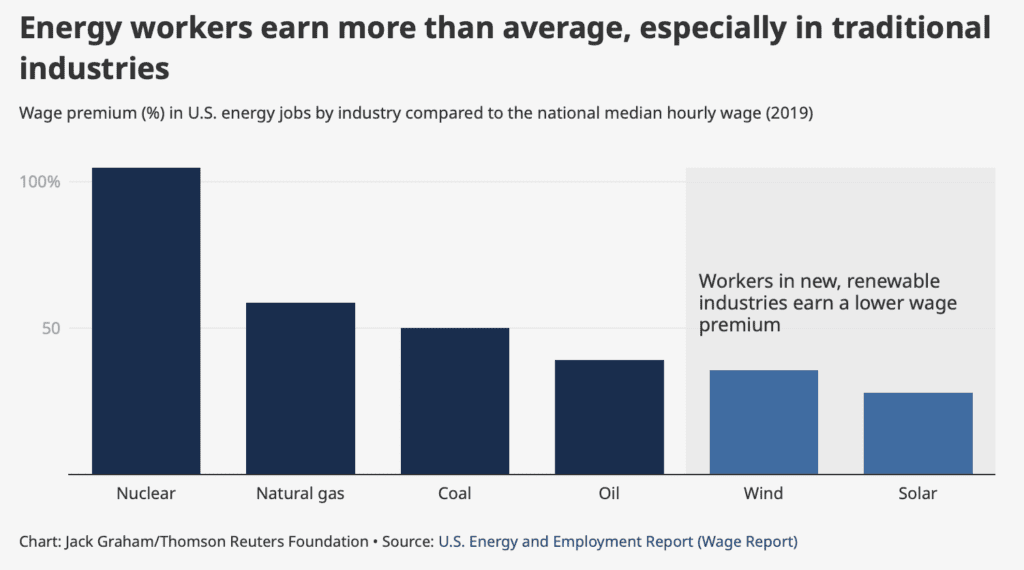

Energy jobs in both new and traditional sectors tend to be more highly skilled and better-paid than the average.

About 45% of energy roles are highly skilled, compared to a quarter of jobs in the wider economy, according to the IEA.

However, workers in coal, oil and gas tend to enjoy higher wages than those in renewable industries.

In the United States, for example, workers in natural gas and coal have a wage premium of 59% and 50% respectively, compared to national median hourly pay, far higher than the 36% for wind and 28% for solar, according to the U.S. Energy and Employment Report.

This may be because traditional energy jobs tend to be more unionised and have benefited from decades of labour representation, while clean energy sectors have a larger share of part-time or contract work, according to the IEA.

This is especially true in emerging markets and developing economies, the IEA said, including in India where coal workers are paid around three to four times the national average.

Analysts also say that more lower-skilled jobs are becoming available as clean energy moves from research and development towards installation and construction of infrastructure.

This shift could mean new clean jobs offer less in terms of wages and security, yet are more accessible to those with lower levels of education.

Can fossil fuel workers transition to green jobs?

The good news for fossil-fuel energy workers is that many of their skills are transferable in a greener economy.

Those working on offshore oil rigs, for example, have many skills that would be useful to offshore wind farms, while project managers for traditional energy infrastructure will likely be well-equipped for similar positions in new industries.

The biggest issue, however, according to the economist Saussay, is that clean energy roles will not necessarily be created in the same places as traditional jobs that were tied to fossil fuel resources in relatively remote areas.

“They tended to be creating highly paid jobs in areas that had high unemployment and low wages,” Saussay added, highlighting traditional industrial regions around the world.

By comparison, clean energy jobs are more spread out and not concentrated in economically deprived areas.

He said this underlines the need to retrain and reskill traditional energy workers, while creating new employment prospects where they live to avoid social dislocation.

“If you don’t put in place accompanying policies, what you end up with is a community that is bereft of economic opportunity,” Saussay said.

This story was updated on Sept. 28 to include a new report from the International Renewable Energy Agency and the International Labour Organization.